Do the Wiggle!

Joel Pomerantz

This article was published in the tubular times, newsletter of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, February 1994.

| see tear sheet | reactions • suggestions • comments |

Like many who were lured to this city by its reputation for social innovation, I spend the majority of my urban existence in the low, central neighborhoods—from the Panhandle area, wrapping around the hills of Buena Vista and Corona Heights to the flats of the Mission. This culturally distinct region of the city was known in the District Election days of Harvey Milk and George Moscone, the late seventies and briefly thereafter, as District 5.

|

graphic: Hoss Rogers |

During the height of my bus-riding days, I used to call it The Land Along the 33, after the historic Muni bus route that winds its way through these political and meteorological microclimates. I would cantankerously insist that there was no point in befriending anyone outside this area for one simple reason: access.

More than anything else (save desire) transportation determines our lives. Proximity and mobility—not just our own mobility, but also that of the goods we produce and consume—limit how we earn our livings, how we nourish our souls and bodies, and even which people stay central to our personal worlds.

(Our language, always a reliable indicator of what's important to us, reflects our constant valuation of physical location and access: notice the psychological sense of the word central in the previous paragraph, or the telling ambiguity of the word convenient—which can mean either easy or nearby.)

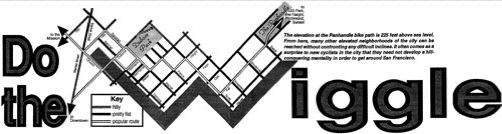

The transit artery that now holds this territory together for me and my subcultural kin is the pattern of streets known affectionately as the Wiggle, or alternately, the Duboce Shuffle. For some decades, bicyclists have found it the best way to get from the low-lying Mission district to the neighborhoods around the Panhandle of Golden Gate Park, or to the Park itself. The route goes up 17th, 16th or 15th Street, turns right on Church Street and then zigzags northwest past Duboce Park toward the Panhandle. Riders from downtown take advantage of this geography, too. The most common approach is up Market to either Duboce or Church. (That approach has one real hill which can be avoided entirely by turning off Market at Valencia and then turning up 15th to follow the pattern described above.)

Hardly a hill to be seen

In following the Wiggle, a rider can stay on roads with inclines so slight as to barely be noticeable as hills—even to visitors from the great plains.

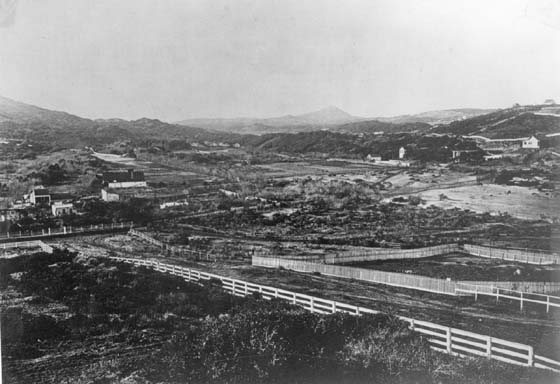

It is no surprise, then, that this route follows an old valley bottom, which, during the rainy seasons of 150 years ago, was a flowing creek bed. Over the millennia, the Wiggle eroded faster than adjacent land because it is a layer of softer material. The eroded area, forming a NW by SE watershed, spilled its outflow into the Dolores Lagoon and Mission Creek through a low point that is now the intersection of Church and Market Streets. The disastrous flood of 1988 that filled the Muni Metro and many basements at that corner testifies to the continued existence of the old drainage patterns.

Before the drainage was relegated to sewers (and transit tunnels!), before the lagoon and creek were filled in, before the Gold Rush and the arrival of the Europeans to the land that is now our mostly-paved home, a year-round Ohlone village rested at a site below Church and Market. This allowed them easy access (there's that concept at work again) to fresh waters of the spring and lagoon, access that was later usurped by the founders of Mission Dolores.

By the middle of the last century, farms had spread through our valley. In 1851, San Francisco annexed the valley as part of the "Western Addition," extending the city's western border to Divisadero Street (so named because it divided the city from the land that was considered part of the Presidio). By the turn of the century, Haight Street had established itself as a business district serviced by a cable car line following the current route of the #7 trolley bus. The farmland had been parceled into grids of 26-foot wide housing tracts and the Wiggle was born as the zig-zaggy, contoured route that connects the central districts.

Wiggle future holds hope

The Bicycle Coalition's long-term, ambitious plan to develop a network of traffic-slowed arteries throughout the city was first worked out at the February, 1993 SFBC retreat, where it was decided that the Wiggle is the most practical place to begin. An already popular bike through-way, the Wiggle is a rare instance of an important connecting route which is not already dominated by high-speed automobile traffic. Also, the neighborhoods are politically progressive, the streets are mostly well-maintained, and the number of trouble spots is small.

On the Wiggle, we have a realistic chance to reconstitute the way traffic flows. The whole route could be a high quality bike corridor with traffic speeds of less than 15 m.p.h. Motor vehicle barricades could limit car traffic to purely local trips, so motorists wouldn't mind waiting behind bicyclists riding side by side. The struggle to create a bike through-way in this especially important access corridor is going to be a political struggle and a major organizing challenge.

The most dangerous stretch of the Wiggle—and our biggest political challenge—is the three block stretch from Scott Street to the Panhandle. For those three blocks, only two streets follow the old valley bed: Fell and Oak (both one way).

While Oak is satisfactory for the eastbound direction (it's slightly downhill so the bicyclist can keep up with motor traffic), westbound Fell Street presents only bad choices for the bicyclist pedaling slowly against the prevailing winds: use the sidewalk for three blocks, ride in the Fell Street Death Monster stampede for those blocks, or detour from the Wiggle up a short hill to the parallel Hayes Street.

One acceptable solution to the Fell Street impasse is to create a protected bike lane along the left side in place of the current parking lane. We expect the new bike plan consultants appointed by the city will consider this option and propose a solution for Fell Street which meets a high standard of safety along the flat contours of the Wiggle.

Our success must be reached at the grass roots level before our plans can become effective city policy. Any person (especially one who lives along the Wiggle) who wishes to help in generating community support for this effort should make herself known to SF Bicycle Coalition organizers at our easy-access (!) phone number, 751-BIKE [it has changed to 415-431-BIKE].

One way or another, the Wiggle will eventually become a creek again, perhaps with a bike path alongside it. This I declare with certainty not because all structures of humanity must crumble someday, though that is a perspective worth keeping in mind, but as a moral imperative. The only foreseeable path by which humanity may continue to eke out community survival requires a renewal of natural elements of the urban landscape—a reworking of our living habits in our little wiggling earth-bound valley.

Sans Souci Valley 1860s looking northwest from what is now Mint Hill at Webster and Hermann Streets in San Francisco. White fence is along Hermann Street. Foggy hill in the far center is Lone Mountain (USF hill). Hill on the right is Alamo Square.

Click on the above image for an enlarged map.

(This graphic is from the original article illustration, made with border tape.)

| see tear sheet | reactions • suggestions • comments |